Thinking about the world from the South, the legacy of the Tricontinental.

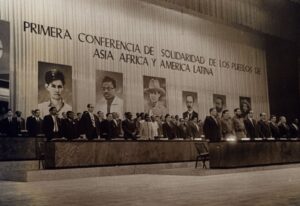

While the world seemed condemned to spin between two irreconcilable poles and the great powers divided up spheres of influence like chess pieces, between January 3rd and 15th, 1966, the Cuban capital brought together for the first time, under one roof and with one agenda, the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America at the First Tricontinental Conference of Havana.

That event, with the explicit aim of challenging the imperial order from its margins, constituted the crystallization of a historical consciousness that understood the anticolonial struggle not as a series of isolated episodes, but as an international front with common roots, enemies, and horizons.

There, principles that today form part of the universal political language were reaffirmed: the right to self-determination of peoples, national sovereignty, the fight against apartheid, the denunciation of racial segregation, and the defense of world peace from an emancipatory perspective.

The choice of the Caribbean as the venue for this first conference was neither accidental nor secondary. Barely seven years after the triumph of the Revolution, the island had become a political and moral beacon for liberation movements in the Global South.

The event positioned it at the center of an alternative political landscape that, in addition to challenging the bipolar order of the Cold War, proposed a third voice: autonomous, belligerent, and profoundly insurgent.

The Tricontinental Conference was also the direct heir of a historical process that began years earlier in Bandung, when Afro-Asian peoples began to articulate their own agenda in the face of the old metropolises and the new hegemonic powers.

The explicit inclusion of Latin America represented a qualitative leap: the confirmation that imperialism operated systemically and that combating it demanded an equally comprehensive strategy.

From this impetus emerged the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL), conceived not only as a coordinating mechanism but also as a permanent instrument of political action, internationalist propaganda, and concrete support for revolutionary struggles.

The magnitude of the conference was reflected in the diversity and influence of its participants. Leaders such as Salvador Allende, Amílcar Cabral, Rodney Arismendi, and representatives from war-torn Vietnam shared the stage with labor, student, and social leaders in a forum where revolutionary experience was debated without euphemism.

The forced absence of Mehdi Ben Barka, one of the event’s main organizers, who was kidnapped and murdered before arriving in Cuba, served as a tragic reminder that the Tricontinental Conference was not merely a theoretical exercise but a dangerous undertaking for the interests it sought to challenge.

The culmination of that intellectual legacy would arrive shortly thereafter, with the publication of Ernesto Che Guevara’s celebrated Message to the Tricontinental, disseminated in 1967. Its slogan—»create one, two, three… many Vietnams»—urged the proliferation of centers of resistance as a means to break the imperial logic.

More than half a century later, the First Tricontinental Conference in Havana remains an undeniable example of the worldview it articulated from its very foundation: the certainty that historically subjugated peoples could see themselves as subjects of history and not merely as stages for foreign geopolitics.

In this profoundly political and radically human affirmation lies the enduring relevance of this memorable event as one of the great moments of 20th-century revolutionary internationalism.

Written by Yadiel Barbón.